I love art because …

- Every object can come in multiple designs. Possibilities are endless. Humans have built shelters, then houses and larger buildings for millennia, yet, shapes, functions and materials continue to evolve and generate novelty. [The doorbell, Liguria, Italy, 2026]

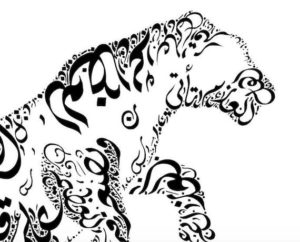

2. Contemporary, abstract art prompts us to ask new questions. It frees our minds from concrete reality, forcing us to rethink our perception of the world. Through intellectual and emotional dialogue between us and the artwork, we construct new meaning. [Gordon Matta-Clark, Conical intersect 3, Paris, 1975]

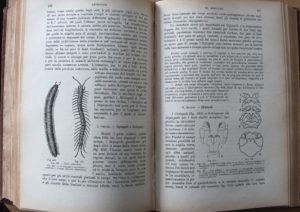

3. Art is present everywhere. Nature in particular is an endless source of exposure to a spontaneous, involuntary form of art. Every shape, colour, pattern, size and movement exists in the natural world. [Trunk and fungi/ Crayfish pincer, Piedmont, Italy, 2025]

4. Art is never annoying. Unlike daily life which can sometimes be tiring, art won’t stop to surprise and amaze us. We can be shocked, enthusiastic, disillusioned or transported to different realities by it. Art can question our current frames of reference, obliging us to let go preconceived ideas. It helps us develop divergent thinking. [Julie Mehretu, Oreironaut 1, 2021-2022]

5. Art is a particularly effective means for personal and organisational change. When approached with an open mind and the willingness to let preconceived ideas go, art will stimulate us to take in new perceptions and messages. These insights may lead to profound, transformative shifts in how we process information, communicate with others or apprehend the complexities of life.

[James Turrell, Skyspace Meeting, MoMa PS1, 2016]

6. Art is a space and a means to challenge society. Art questions its accepted norms, behaviours, models of expression, policies and values. Art has the potential to be revolutionary, to upend the status quo. That is an immense power that authoritarians fear. They will try to erode the freedom, intrinsic to creativity. Should art cease to ask difficult questions, it would die or lie dormant, waiting to awaken with new, transformative propositions. [Takahiro Iwasaki, Out of Disorder – Mountains and Sea, Japanese pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2017]

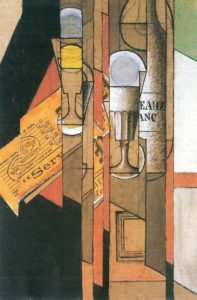

7. Art is not confined to aesthetics. In many ways, it is defined by its ability to transcend conventional beauty. Pure beauty often serves as a confirmation or reinforcement of existing norms. When those norms are challenged, the notion of aesthetics is disrupted and will evolve. Igor Stravinsky’s premiere of the Sacre du Printemps (1913) was booed out loud. Today it is no longer raising an eyebrow.

[Olafur Eliasson, Riverbed, 2014]